- Supreme Court justices serve a life term once nominated and confirmed by the US Senate.

- Whenever a Supreme Court justice retires or passes away, there is often a political debate about nominations and the court’s ideology.

- While some think term limits could discourage justices from retiring with political motivations, and encourage fresh perspectives, this is not necessarily the case.

- Matthew Stanford, a California attorney, says term limits would not depoliticize the retirement or selection process.

- Instead, he suggests that age requirements could better solve some of these issues, while maintaining a core feature of the Supreme Court: the relative lack of volatility.

Whenever a Supreme Court justiceretiresorpasses away, the conversation inevitably turns to term limits. As it should:Most votersfavor capping justices’ time on the Court, and it has rarebipartisan appeal. Even the current chief justice endorses the idea-or at leasthe did.

The supposed benefits of term limits are alluring. An18-year, non-renewable term, for instance, would make vacancies more predictable, granting each president two nominations per term. Assuming nobody dies or retires, no single president could handpick a majority of the Court.

Possible consequences of steady turnover provide additional fodder for term limit proponents: theoretically, term limits would end socially disconnected rulings and politically motivated retirements, and increase the likelihood of a court with an array of ideologies and fresh perspectives.

But let’s consider the possible benefits realistically.

It's likely that term limits would not prevent politically motivated justices from retiring during a favored administration, even by cutting their own terms short.

In fact, scheduling two vacancies per term could actually make this more appealing. Using the current composition of the Court as an example, consider the following hypothetical:

Justices Ginsburg and Breyer have terms that are set to expire before the 2020 election. Assume that the current administration is expected to lose reelection. Preferring not to have their seats filled by a Democratic president, Justices Thomas and Alito, whose terms will expire after the election, retire early. The outgoing president would get two more nominations at the expense of the next administration.

It's easy to imagine the political turmoil that would ensue - especially in light of theemergent viewthat vacancies created in an election year should only be filled after the ballots have been counted.

And plugging this loophole would be tricky. As recent events might suggest, if there were an unexpected vacancy on the court before the end of a presidential term, neither law nor custom could prevent a determined Senate from nominating a candidate that aligns with their ideology and filling that vacancy before the next inauguration. Only a constitutional amendment could do that.

Otherwise, retirement games wouldn't simply persist; they would worsen. Ironically, term limits would raise the stakes.

Nor is an increase in ideologies or perspectives a given.

Term limits won't depoliticize the selection process - it won't prevent either party from using its preferred litmus tests for identifying potential justices. There is already ample concern aboutnominee reluctanceto discuss candidly their legal philosophies at confirmation hearings. Term limits might create predictable vacancies, yet it's still largely unknown how that could impact prospective nominees

One thing term limits might reduce is the perceived disconnect between the realities of life-tenured justices and ordinary citizens.

But this problem is only partially related to the length of a justice's term, and it assumes that age is a reliable proxy for social consciousness.

Even if that's true, most of the blame belongs elsewhere-namely, the custom of nominating Yale and Harvard graduates holding some combination of prestigious practice, judicial, and/or academic positions. Term limits would do little to bridge the gap that makes the Court seem so otherworldly.

Still, the term limit discussion does raise an important consideration: modern life expectancies. Though undeniably a good thing, longer lifespans mean longer terms for justices. As Erwin Chemerinsky, Dean at Berkeley Law and a constitutional law scholar,explainedin The New Republic:

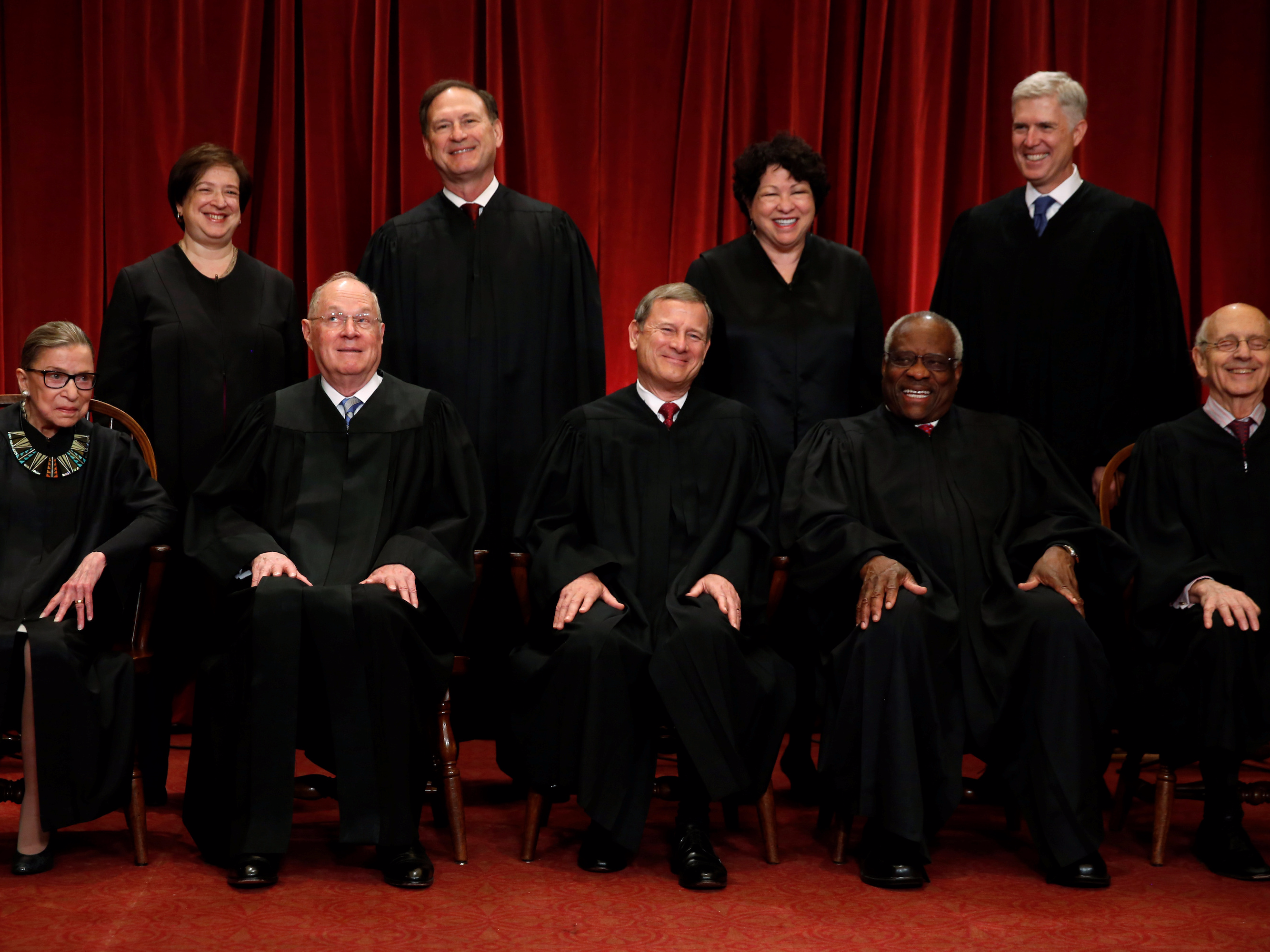

"Life expectancy is dramatically longer today than when the Constitution was written in 1787. The result is that Supreme Court justices are serving ever longer, with the last four to leave the court having served, on average, for 28 years. This trend is continuing with the current court. Clarence Thomas was 43 when he was appointed, and John Roberts and Elena Kagan were each 50 at the time of their appointments. If these justices serve until they are 90-the age at which Justice John Paul Stevens retired-they will have been on the bench for upwards of four decades apiece."

Even assuming, as Chemerinsky seems to suggest, that longer terms are somehow antithetical to our constitutional system, a more modest revision would address this concern, and it would do so without sacrificing the judicial independence that motivated the Founders to include life tenure in Article III of the Constitution.

In fact, other provisions of the Constitution already include such a safeguard: age requirements.

One must be 35 years old to run for President or Vice President, 30 for Senator, and 25 for Representative. (Whether those numbers ought also to be lifted is a discussion for another day.)

If providing a counterbalance to longer life expectancies is the core rationale for term limits, a minimum age-perhaps 60 or 65 years old-could accomplish this without the unintended consequences that term limits threaten.

It also would likely be an easier reform to implement. Although a constitutional amendment would be the most ironclad approach, a statute or even a custom establishing age requirements would likely suffice.

Finally, term limits would eliminate a consequence of life tenure, intended or not, that has become a unique, arguably essential feature of our constitutional republic: the relative lack of volatility, for which the Court is valued.

The Court is insulated from more direct forms of democracy. The elevated role of precedent in the work of the Court underscores this point. Even as the Founders were careful to avoid establishing anything resembling the British Crown, they nevertheless included life tenure in the 1787 Constitution. They presumably understood this to mean that justices and judges alike would largely remain in office for the remainders of their careers. Yet they included it anyway. Age, it would seem, was seen as an asset to the work of the judiciary, a feature of judicial independence rather than an oversight only recently brought into focus by improved life expectancies.

Term limits would abolish this feature despite their more modest purpose. A minimum age requirement would not.

The United States has the oldest written constitution still in use today. It is not enough to demand term limits simply because we are the only democracy that extends life tenure to its judiciary.

Before we proceed to jettison the order of constitutional elders that life tenure has effectively molded within our courts over the past 229 years, we would be wise to consider this less drastic alternative.

Matthew Stanford is a California attorney and Senior Research Fellow at the California Constitution Center. He is a graduate of Berkeley Law and Penn State University.